What do you do when the guy who recruits you is gone and the Head Ball Coach wants to change your position? Nowadays, that equates to an instant portal entry, but for Anthony Lambo, Virginia Tech lineman in the 1996-2000 seasons, it meant adversity. And for this Essex County, New Jersey kid, there was no backing down from a fight.

Make no mistake about it – the transition from playing defensive tackle with reckless abandon to learning the footwork, hand positions, and other important techniques of the offensive line were a challenge that caused a lot of struggle for Lambo. But if you knew his background, you also knew that he was going to work his tail off to make it happen. And he was going to do it because the team needed him to be successful.

It’s hard to imagine a college athlete today with a similar story. That is why Anthony Lambo is a real throwback, a perfect fit to the culture that Frank Beamer built at Virginia Tech. Lambo overcame adversity when his coach left and he was moved from defense to offense. He worked hard to learn his new position, then he excelled at it. Above all, he put the team before himself. Where can you find that in today’s college football landscape?

Toughness and Work Ethic Built in Essex County, New Jersey

Anthony Lambo was born in Newark, New Jersey and lived there for nine years in a one-bedroom apartment with his parents and older sister. His father, a United States Army veteran, was a police officer in Irvington, a tough neighborhood bordering Newark to the southwest. Like many others at that time, his mother was a stay-at-home mom, but that would change after a younger brother was born (when Lambo was 6 years-old) and she worked as a cashier and as a waitress.

When Lambo was 9, and after three years of living with five people in a one-bedroom apartment, the family packed up and moved just a few blocks across the northwest border of Newark and into Bloomfield. Not only was he happy to be in an actual house, but the young and free-spirited Lambo was thrilled to be out of a Catholic school and no longer wearing a tie to class!

Lambo would thrive in Bloomfield, a blue collar, working class town. He was very active and loved being outside. A self-proclaimed “energetic” child, he played many youth sports, from football to basketball to baseball to soccer to wrestling. Basketball became his first love, but then he was “forced” into football because of his size. “Back then, it was like, ‘You’re big, you’re gonna play football’,” Lambo remembered others telling him.

Because he was bigger, Lambo often played with older kids. This challenge of playing with older kids, coupled with the social norms of the playgrounds of Bloomfield, helped develop a toughness in the young Lambo. “When you’re playing older guys,” he mused, “you either get better, or you get kicked off the court.”

As he entered high school, his size and physical maturity set him up for success in athletics. As a freshman, he earned a varsity letter as a pitcher on the baseball team. As a sophomore, he lettered in both basketball and football, as well as again in baseball. He eventually left the diamond, but he stayed with the other two sports, earning 9 total varsity letters.

Despite a future in football, which he really did not realize until later in high school, Lambo still loved basketball and he put a lot of effort into the sport. Who could blame him? After all, this was Bloomfield High School, the same school that put Kelly Tripucka and Alaa Abdelnaby into the NBA!

(author’s note: Bloomfield High School has an impressive alumni list of professional athletes and media personalities, including ESPN’s Bob Ley and Anish Shroff, as well as Kevin Burkhardt, Frank Tripucka, and Charlie Puleo, whom the Mets traded to reacquire Tom Seaver in 1983!)

Lambo played basketball throughout his four years of high school, earning all-conference honors his senior year. By that time, though, he knew football was his future, and the colleges were also onto him.

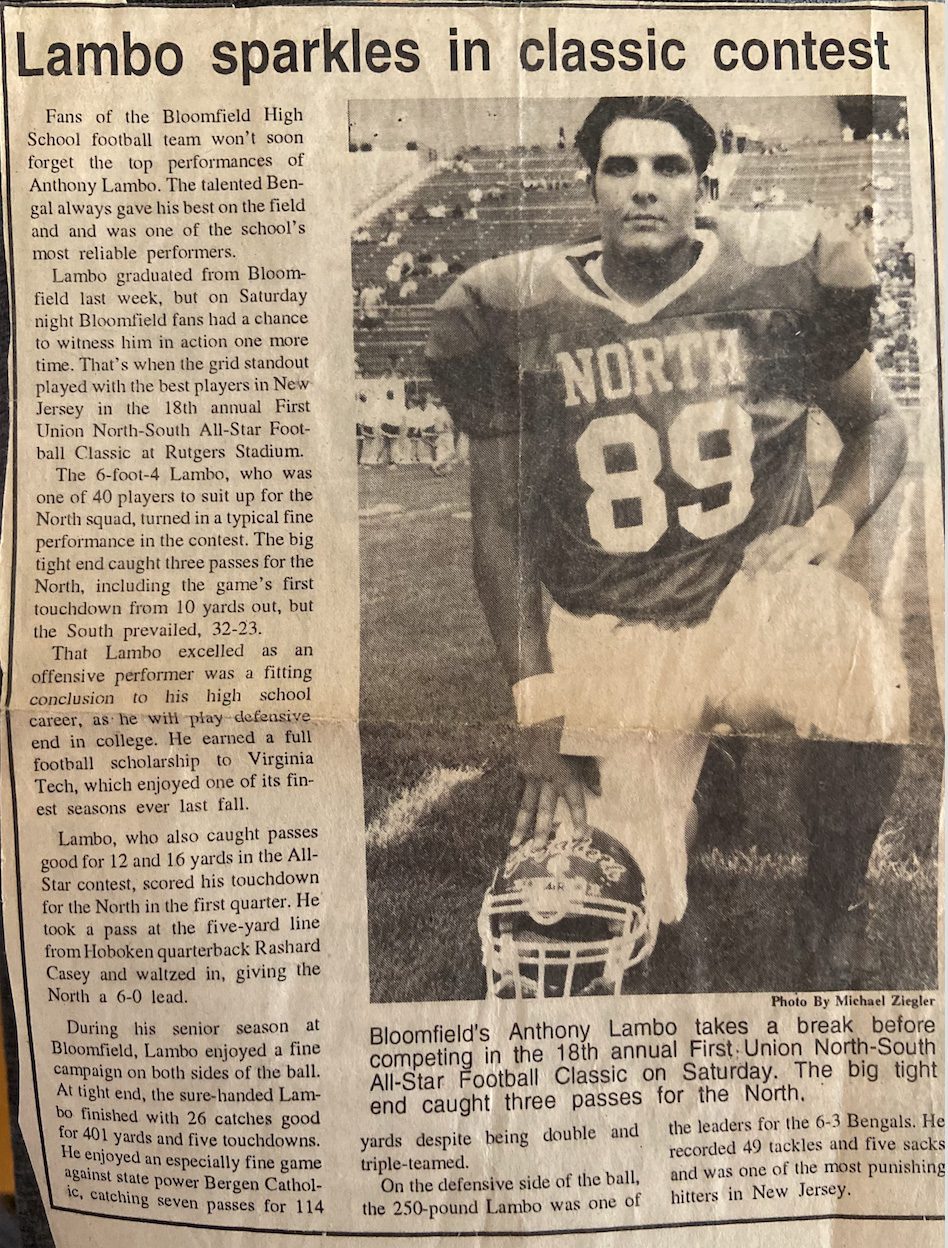

An all-state and honorable mention USA Today All-American tight end who also thrived at defensive tackle, Lambo was a much sought-after prospect as a senior in the fall of 1995. At least 30 Division I schools, many who are now in the Power 5 conferences, offered him a scholarship. However, most of those schools wanted him to play on the offensive line, and he wanted to play on the defensive side of the ball.

Virginia Tech’s Lunch Pail Defense Comes Calling

Because Virginia Tech was one of the few schools recruiting Lambo to play defense, he was really interested in the Hokies’ offer. During his recruitment, he met Bud Foster, and J.C. Price was one of his hosts. Lambo was impressed by the family atmosphere. “It felt like home while I was there.” That was enough for the big guy, and he signed on to play for Foster’s budding Lunch Pail Defense.

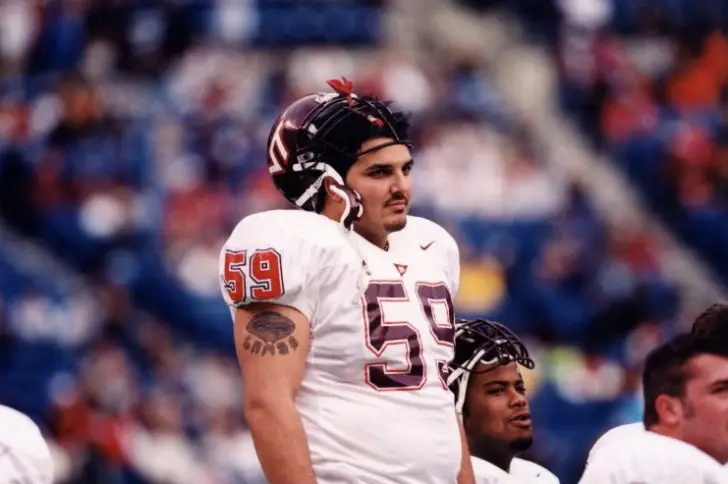

Like many freshmen interior linemen, Lambo needed a redshirt year to get his body – and mind – ready to play at this level. “It was eye-opening when the varsity guys came in,” he said, “and I’m trying to pass rush Todd Washington, who’s 23 years old and a grown man and about to be a draft pick.”

“My freshman year, I learned a lot,” Lambo reflected. In his first practice, going against the older guys, he was knocked on his back side by Washington. “My tailbone, it was sore for about three days,” he confessed. He also admitted that it was the first and last time that he ever was knocked on his back side in five years of college!

He went on to remember the bigger lesson learned that day. “This is not high school, where you’re the best athlete, and you can get by just being athletic,” Lambo said. “You gotta bring it every single snap. If not, the day was not going to end well for you.”

So he went through the year learning from the older guys and doing his part to get better. Little did he know how much better this year would make him as he also spent time that season, ironically, on the scout team as a tight end, blocking All-American Cornell Brown day in and day out!

By the start of the 1997 season, however, Lambo was ready to go. The opener was a road game against Big East foe Rutgers. Lambo was going to play his first college football game in Piscataway, New Jersey, approximately 30 miles from his home town!

It was both exciting and overwhelming for the redshirt freshman, who had about 25 friends and family members at the game. “During warmups, I felt like my heart was going to explode out of my chest,” he recalled. He was backing up fifth-year defensive tackle Kerwin Harrison, but the game got out of hand early (a 59-19 Hokie victory), and Lambo saw plenty of action. In approximately 25 snaps, he registered 6 solo tackles, 3 assisted tackles, and 1 sack!

A Surprise Position Change

Lambo did not have much time to celebrate the Rutgers win and his impressive debut. The very next day, he was called into Head Coach Frank Beamer’s office. “Coach Beamer sat me down,” Lambo remembered vividly, “and he basically said, ‘We love what you’re doing, we love how hard you work, you’ve got great feet. We feel that your skill set will benefit us on the other side of the ball’.”

Stunned, Lambo took a minute to let it sink in. Then he responded. “I respectfully told Coach Beamer that I came to Virginia Tech to play for him and to play defense for Coach Foster,” recalled Lambo. “And I would appreciate if you would give me the opportunity to finish the year on that side of the ball.”

Beamer understood Lambo’s plight, and he did admit that they told Lambo that he was coming to Tech to play defense. But Beamer also knew that they had under-recruited at offensive line, and some of the most recent recruits were not ready to play, so they would readdress the issue in spring practice.

He wasn’t happy, but Lambo understood that the team needed him to make the move, so he did it. “I did what was best for the team,” he said, “instead of doing what was best for me.”

A Tough Transition to Offense

The following summer, in camp for the 1998 season, Lambo had fully transitioned to the offensive line. He worked hard in the preseason and earned the starting job at right tackle for the opener. However, the redshirt sophomore suffered an ankle injury in the first game, and, after recovering, he found himself as a backup to both tackle positions as well as the right guard.

This was a tough pill to swallow for a guy who always had athletic success. “It was the first time ever in my life since the age of 7 that I wasn’t starting,” Lambo revealed, and it was frustrating. Compounding his struggle was the response he got from his position coach. “He told me I needed to practice harder, which was difficult because I was still learning how to practice and still learning technique.”

Lambo felt alone. Todd Grantham, who had been the defensive line coach that recruited Lambo to Tech, was long gone. And now he had a position change – one where he sacrificed his own interests for the team’s needs – but then dropped on the depth chart and was playing fewer and fewer snaps as the weeks went on.

He still had that free-spirit, that twitch that made him good as a defensive lineman. Yet here he was, in a new position that required much more control, more footwork, more technique, which went against his nature. He admitted, “I wasn’t physically ready to play the position. My technique was terrible.” It was a dark place for the big man.

Fortunately, he knew to be patient, recalling the wisdom of his father: “You do what’s expected of you, you work hard, and then you wait for the results.” Also, he was from Bloomfield – that blue collar work ethic was ingrained in his identity. That playground “get better or get off the court” mentality took over, and there was no way that Anthony Lambo was not going to be successful at what he did.

Cohesion on the Offensive Line

In reflecting on that success, Lambo points to his previous years as a defensive lineman. He feels that his experience as a defensive tackle prepared him for the offensive line because he knew what those defensive guys would think or do.

He also credits the defensive studs from Virginia Tech because to Lambo, blocking Corey Moore and John Engelberger was tougher than blocking most other guys that he would face on Saturdays. “It was good for me because I was learning by practicing against the best. So when we did get to games it was like a walk in the park.”

Lambo would go on to start his junior year alongside Matt Lehr, Keith Short, Josh Redding, and Dave Kadela. This unit played together for over two seasons, building great chemistry and camaraderie. This gave them an advantage and they performed at a high level. “We basically didn’t have to say anything to each other, we just knew,” Lambo said about getting to the line of scrimmage with his peers. And they were unselfish. “We didn’t care who got the credit.”

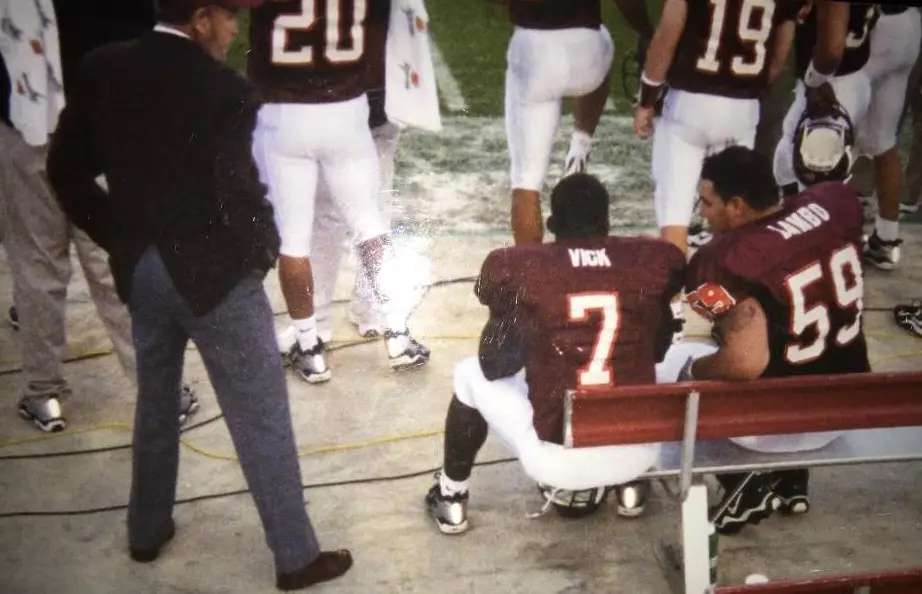

Blocking for Michael Vick

Lambo and his offensive line mates had the honor of opening holes for some quality runners in Virginia Tech’s recent history of excellent running backs. Shyrone Stith ran for 1187 yards in 1999. Andre Kendrick backed him up well, gaining 714 yards that year and 547 the next. Lee Suggs ran for 1207 yards and 27 touchdowns in 2000, leading the nation in the latter category. And then there was Michael Vick.

“I knew his first couple of practices that he was a special kid,” said Lambo about Vick. “When Mike was redshirting, he did a lot of things that reminded me of one of my favorite athletes, Bo Jackson.” Lambo recalled how Vick did things in practice that left people in awe. “He shouldn’t be doing that stuff at 18 years old.”

Lambo appreciated the opportunity to play with someone like Vick. “He’s a once in a lifetime, world class athlete.” However, because of that athleticism, blocking for him wasn’t always easy. If a play was designed to go in one direction, Vick could easily – and quickly – improvise when needed and be somewhere totally different in a split second. “Do you know how hard it is to block for someone who you have no idea where he is going to be?” Lambo quipped.

Also, defenses schemed differently for Vick. In one game against Boston College, the Hokies ran 74 offensive plays. Lambo recalls that about 90% of them included stunts or blitzes. Blocking with such unpredictability – by both the defense and his own quarterback – created an added challenge.

However, Lambo and his line mates were up to those challenges, as they opened holes regularly, allowing the team to rush for close to 3,000 yards in both the 1999 and 2000 seasons. They also protected Vick well enough to allow him to become a Heisman Trophy finalist and the NFL’s first overall draft pick in 2001.

On to the NFL?

Anthony Lambo finished Virginia Tech with quite an impressive resume. In addition to being a two-year starter and four-year contributor, he lead the team in knockdowns his junior year and finished second his senior year. He also blocked for some productive Virginia Tech players, sharing in their accomplishments.

He had a memorable post-season run as well. He was, arguably, part of the best five-year bowl-string in Hokie history. As a redshirt, he was part of an Orange Bowl team, then he went to the Gator Bowl, the Music City Bowl, the Sugar Bowl – and National Championship game, and the Gator Bowl again (which should have been a Fiesta Bowl, but sigh, I digress).

With his degree in hand, he was ready to try his luck at the next level, the National Football League. Virginia Tech hosted a Pro Day and Lambo worked out with his left guard Matt Lehr. Lambo believed he had a really good workout, with his 4.72 time in the 40-yard dash highlighting the day.

However, at 6’3”, he was a little below the average height of NFL linemen, and admittedly, he was still honing his craft, having only moved to the offensive line a few years prior. Lambo was confident in his athleticism and hoped to be picked up in the later rounds. “If you look at my tape,” he said, “my technique was not great but my production was outstanding.”

Unfortunately, Lambo did not hear his name called. His dream was still alive though, as Cleveland, San Diego, and Baltimore showed interest in him as an undrafted free agent. He and his agent deliberated, and in the end, Lambo chose to sign with Baltimore. He liked that the Ravens played a similar style to the Hokies, that they were closest to home, and that Cornell Brown and a lot of former Big East players were on the team!

He started with mini-camp and did well. On the very last day, though, he was informed by the team management that they were concerned about an old shoulder injury and were not inviting him to summer training camp. Lambo was devastated. He played with that injury through four years in college and never missed a game because of it, and now the Ravens were telling him that it was the reason he was being released from the team.

No other opportunities presented themselves, and for the first time in his life, Lambo did not know what to do with himself. “My whole life I played sports year-round,” Lambo reflected. “That’s all I knew, that’s all I did. And it just stopped.”

Fortunately for the former Hokie, because the injury occurred during a bowl game and he was less than two years removed from playing in Blacksburg, he was still covered by Virginia Tech’s insurance. He was able to return to campus to have surgery to repair his shoulder! While he was there rehabbing, he decided to finish his master’s degree.

It was during this time that he pondered his situation. “What am I gonna do?” he asked himself. “Am I gonna do this the rest of my life?” He was referring, of course, to the frequent injuries of NFL linemen and the probabilities of more surgeries and more rehab.

That is when he had his moment of clarity. “I knew in my heart, I was athletic enough and mentally and physically tough enough to play in the NFL. And at the end of that school year, that was good enough for me.” Just like that, Lambo chose his health over the NFL.

A New Path in Life

For a guy whose life revolved around sports, it was a no-brainer for Lambo to continue that involvement within a career. “I wanted to get into coaching,” he revealed. “I loved sports, that’s what I did my whole life. I wanted to be around that energy, that type of kid.”

He received a call from the head coach at Kean University in Union, New Jersey, and that is how he landed his first job – coaching college football. However, he quickly learned that he could not support himself on the meager stipend of a Division III coach – $3500!

He had to find a career, one that would allow him the opportunity to coach. After speaking to several peers and hearing them recommend education, Lambo became a teacher. “Teaching kind of called me,” he said, reflecting on his past teachers and coaches, thinking of what he learned from them and how he could make an impact on young lives.

A Teacher and a Coach

That next year, he landed a full-time teaching job in south Jersey. However, the toll of a year of early rising, very long commutes, and late practices was too much, and Lambo returned home. He took a job at Bloomfield High School as a physical education teacher, and he coached three sports: football, basketball, and track.

BHS was again good to him, and he was there for five years, but financially, there were better opportunities elsewhere. Now that he was married and with a child, financial planning became much more important. A former BHS colleague told him of an opening at a high school in the more affluent Bergen County, and Lambo was on the move again.

Unfortunately, budget cuts cost him that job in 2011, but he landed on his feet when another personal contact helped him locate a job in the West Essex School District, where he now teaches phys ed in the middle school. Over the past 12 years in West Essex, he has coached football, basketball, and track for the high school, and he has also served as the strength and conditioning coach, overseeing the weight room.

Now, however, he only coaches one sport. He chose to give up the others because of the demand they require of his time. With his kids getting older and becoming very involved in their own sports, he admitted that wants to be more present for them. “I have three girls, and as a dad, I felt like I need to be around.” So after 18 years of coaching so many sports, he now just coaches track.

That said, he still is able to reap the benefits of his time as a teacher and coach. Frank Beamer’s influence is strong in him, as Lambo really values the relationships he has built with his students and athletes over his 20-year career in education. “I’ve been to baby showers of some of my former athletes and some weddings,” remarked Lambo. “I have great connections. It’s all about building relationships.”

Keeping his Bloomfield Roots

Although Lambo now lives in Morris County, New Jersey, he still has strong ties to his hometown of Bloomfield. While he was teaching at BHS, he began a relationship with his eventual wife Desiree, who is also a Bengal alum. She was also a very accomplished athlete, having earned 12 varsity letters at BHS and going on to play softball at St. Joseph’s in Philadelphia.

He and his wife also lived in Bloomfield briefly, but as their kids got older they decided to move west in the hopes that their children could develop their own identities and not be known as “Lambo’s kids” or “Desiree’s kids.”

But that didn’t stop him from giving back to the community that helped him become who he was. In 2011, right after he was let go from his teaching job at Northern Highlands High School, he talked to former teammates Keion Carpenter and Andre Kendrick, both of whom were very involved in philanthropic efforts in in their own towns. This gave Lambo the inspiration to do something for his own town of Bloomfield, and thus, the Bloomfield High School Football Alumni camp was born.

Fast forward 12 years later, and Lambo continues to run this free camp for Bloomfield kids in grades 3 through 9. This year, 71 boys and girls registered, and numerous BHS alumni who played college football came back to work the camp. Lambo has received great support from the community to help offset the costs of the camp and he is proud of the success of the event. “We’ve probably had about I’d say well over 3,000 kids over those 13 years come to that camp for free.”

The relationship with Bloomfield is reciprocal. In addition to the tremendous support Lambo gets for his one-day camp, he has also been recognized for his contributions to the town and the high school. He has been invited back to work at coaches’ clinics, and he won a community service award in 2011. He was also inducted into the Bloomfield High School Hall of Fame in 2014.

Once again, the Virginia Tech influence is very obvious in him. The school motto – Ut Prosim, That I May Serve – is something Lambo clearly takes to heart.

This is Home

For Lambo, his family and his home life are his priorities. After so many years of coaching other people’s kids, he now is enjoying life as a dad in the stands during his three daughters’ competitions. These three daughters happen to share an August birthday month with his mother Mary, something that makes Lambo’s heart smile.

This new life is the best of both worlds, because he is able to pass on those valuable characteristics of toughness, work ethic, and sacrifice at home and just be a fan in the bleachers during games. He and his wife of 16 years do have their hands full with the soccer and basketball schedules of their three active children, but there is no other place he would rather be!

And those kids, who are very athletic like their parents, are indeed making names for themselves. His oldest daughter is a rising junior in high school, and last year she started for her high school basketball team, earning first team all-conference honors. She helped them win the conference championship, then a State Sectional title before they came up just short in the State Group III final. At 27-3, they made it further than any other girls’ basketball team in school history.

The younger twins, both in middle school, also found success on the hardwood. In their first year of recreational basketball, they won the league championship. Their mother was their coach, giving the team three Lambo’s to lead the charge!

When Anthony Lambo has the time, which he does in the summers, he loves to play golf. He calls himself a “bogey golfer,” with a 17 handicap. As he has aged, he has embraced the patience that the sport demands. “The thing I love about golf is that every swing is a mental and physical challenge,” said Lambo. “It is something that allows me to get out in nature and still be competitive.”

Despite his busy schedule during the school year, he still finds ways to visit Virginia Tech. He is friends with Coach J.C. Price, and he knows Head Coach Brent Pry, who was a graduate assistant for the defensive line during Lambo’s redshirt-freshman year as a defensive tackle. He loves to get back to campus and give his family that game day experience in Blacksburg.

Credit for his Success

Anthony Lambo was a gifted athlete, yes, but he worked very hard for his success. He also sacrificed of himself for the greater good of his team. “At the end of the day, your teammates come first,” he still believes. And a lot of those lessons learned through his playing days translate to the real-world life that he now lives.

Lambo was fortunate to have other positive influences on his life, and he recognizes them and what they did for him. One such influence was his own father. Living with a police officer as his dad really helped Lambo learn at a young age the importance of working through adversity, as well as making good decisions. Lambo is grateful for those lessons, and he acknowledges how growing up, he often made choices that would make his parents proud as well as make his family name better.

Playing for Frank Beamer only added to those core values that Lambo cherishes. Beamer was great at indirectly teaching people how to be humble and how to treat people well. The Hall of Fame coach was a master at building relationships, but he was also terrific at helping teenagers become men. Lambo sees clearly how Beamer and Virginia Tech helped him in his personal growth.

“I’d say my time at Virginia Tech,” Lambo contemplated, “kind of molded me into the man that my dad started molding me into. And when he kind of let me go and they took over his job basically, they did a great job of teaching me the right way to do things in life.”

And that is Anthony Lambo. He works hard, he focuses on the little things, and he does things the right way. He is a good father, husband, teacher, and coach. He treats people well and develops positive relationships.

It is no surprise that he was so successful on the Virginia Tech gridiron, and it should be no surprise that he is so successful in being the person he is now. He is yet another great example of the legacy of Frank Beamer’s football players representing the school and program well, paying it forward, and just being good people!

And if you ever get the chance to talk to Anthony Lambo about Hokie football, do it! You won’t regret the few hours of hearing such colorful stories of our favorite football team!

To read more of my articles on Virginia Tech football, click here.