In this edition of homicide brides, we will cover the tragic homicide, and self-murder of Martha and Jim Tyrer on September 15th, 1980. This is the earliest homicide (and self-murder) covered so far in this series – this story is for you, history buff!

Jim who?

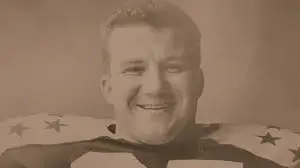

Our memories are short, and years are long. It’s easy to forget players playing this past season, much less an athlete who died before many readers were born. Jim Tyrer is one of the most talented players of his time. However, due to the circumstances surrounding his passing, he is often left out when stories of the greats are told.

Early life

Not much is known about Jim’s early life. He was born on February 25th, 1939, in Newark, Ohio. He has at least one sibling, his sister, Lucy, who loves him very much and keeps a photo of him on her wall, thinking about him regularly. Tyrer was a football and basketball star in high school, graduating in 1957. A long-time friend described Jim as easygoing, and a coach’s dream.

Jim Tyrer attended college at The Ohio State University, where he had All-American honors and was coached by Woody Hayes, obtaining his zoology degree. His long-term friend recalls being unable to attend most of Jim’s college games but described him as humble and giving, visiting his friend’s son in the hospital after surgery anyway.

NFL

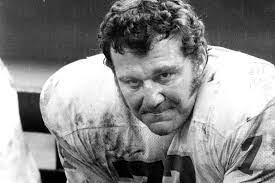

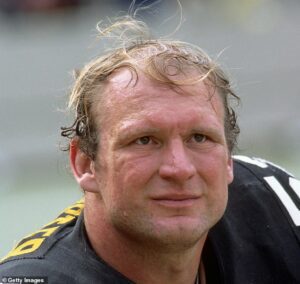

Jim Tyrer was a force to be reckoned with on the gridiron – he was a 6″6″, 280-pound offensive lineman, enormous by 1960s football standards. Jim was a Super Bowl champion, two-time pro-bowler, a member of the All-AFL team eight times, and was voted in the AFL All-Time Team. Tyrer is also a member of the Kansas Chief’s Hall of Fame. The legend played 14 seasons in this high-impact role from 1961-1974, thirteen with the Dallas Texans, who became the Kansas City Chiefs, and one with the Washington team, now referred to as the Commanders. Jim played 180 games in a row, starring all of them. He missed two games in his career.

Controversy swirls around Jim Tyrer not being a member of the NFL’s hall of fame. Countless players of the time will attest to him being one of the best left tackles ever. Some say this is because of the circumstances around his and Martha’s death; some say it is because AFL players are often overlooked or looked down upon by the NFL. As of 2010, out of the 11 HOF offensive tackle inductees, Jim had more accolades than nine and a comparable amount to one.

This is a bit questionable, considering the NFL has reiterated that a person’s induction into the Hall of Fame is based solely on what they do on the field, not their life choices. The Hall already has offenders of a sexual nature, proud racial segregationists, and people charged with but not convicted of double homicides. Once someone is inducted, they cannot be taken back out.

What makes Jim’s crimes the moral boundary for entry into the HOF when he is qualified based on his on-field performance? It feels odd to discuss a homicide and the Hall of Fame in the same article, but this is something that his children and many people from that era of football feel strongly about.

Style of play

Jim Tyrer was one of the biggest football players on the field at the time. He had the largest head in college football and the AFL. He was nicknamed the Pumpkin after a teammate carved a huge pumpkin, cut up red fabric into hair, and put it on the 50-yard line, saying it was Jim. Tyrer had a good sense of humor about it, even when teammates joked his wife would rent his “head” out as a Jacko lantern for kids on Halloween.

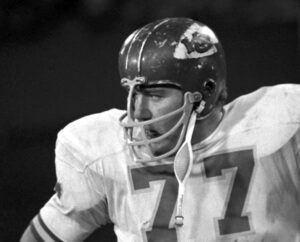

The trouble was that it was hard to fit the “Pumpkin” with a helmet. A teammate described Tyrer’s headgear as a big red trash can. No helmet was ever quite big enough for Jim, so they would remove the padding and extra suspension built into the helmet, leaving roughly half an inch of padding to protect his head on impact. The helmets of the 1960s and 70s weren’t good protection in the first place.

When Tyrer was in the league, tackles were prohibited from using their hands. Instead, players would form what was described as a chicken wing shape with their arms, encouraged to lead with their helmets, which was called their weapon. Players who tackled others regularly often had gashes and ridges on their foreheads.

Tyrer described what he felt an offensive tackle had to be – orderly and disciplined, taking every hit like a hockey goalie, with a sort of passively violent anxiety. When it was your turn to hit someone, you released that energy onto them. Jim was a tree with the grace of a ballerina and quick feet. Every collision he landed would feel like a haymaker to the sternum, according to his opponents.

Jim rammed his head into people fearlessly. He didn’t really have a choice – all players would find themselves on the chopping block if they didn’t play through concussions and injuries. A former teammate suspected that Tyrer probably had a “handful of concussions” throughout his football career. Either that player meant a handful of concussions each game, or he had one too many himself. Using one’s head as a battering ram could introduce head trauma each and every play. Tina recalls her father experiencing frequent headaches during his football that he attributed to the tightness of his helmet, consulting a doctor.

Personal life

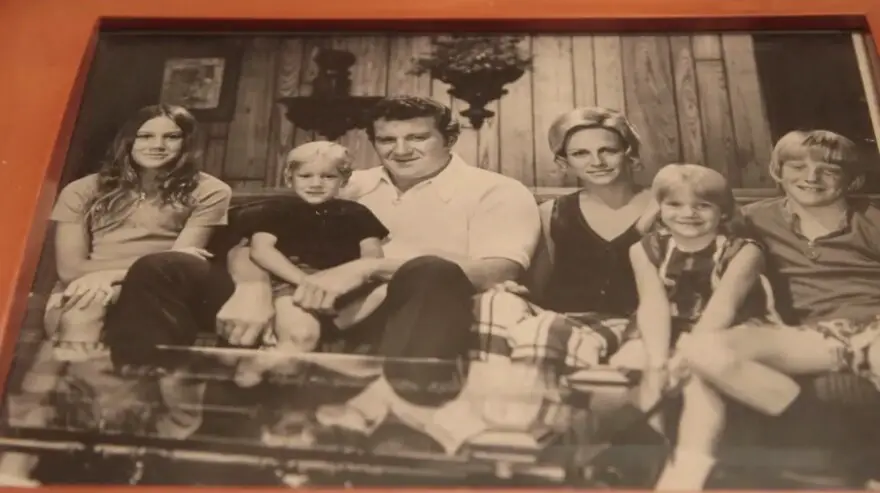

Jim Tyrer was a husband and father of four. Martha and Jim married early in their 20s, and appeared to have a boring, happy marriage. Jim bonded with all four of his children – Tina, Brad, Stefanie, and Jason. He described them as all being so special. Tina was in college, and the rest of the children ranged between 17 and 11. His youngest son remembers his dad as loving, albeit not affectionate, which was the norm for fathers of the 60s and 70s. Tyrer would go on outings he planned with his children and attend their sports activities when he wasn’t working.

Martha and Jim shared traumatic life experiences surrounding their fathers. It likely was something they bonded over. At age 20, Truman Cline was in a car wreck and lost three out of four limbs. He went on to get his masters in engineering, not slowing down. Tyrer’s father died suddenly at one of his basketball games in high school – Jim played the following week anyway. The couple also felt strongly about their children’s education, deciding private school was a must. Nothing else was said about the couple’s relationship.

Teammates remember Jim as hard-working, intelligent, forward-thinking, sensible, a pillar of strength, and possessing strong business aptitude. He was always true to his image – for example, he was always a Waffle House type of guy, not someone who wanted to show off eating at a Michelin restaurant. He only got drunk once in his football career that friends knew of – and it was when his team won the game that would put them into the very first Super Bowl. Some say Jim lived a little out of his budget – he had a large house, and his children’s education bill was high.

Historical Note

It was not until 1980 that players started getting real money. Before that, playing football was like a part-time job that didn’t pay particularly well. Everyone had side jobs (including Jim). Pensions were first available in 1968, and the NFLPA became a certified union in 1970 for the first time. NFL owners were frustrated by advancements like free agency in football and player benefits and protested them extensively – coming head-to-head with the union often. Some things never change.

As the rules are now, players can begin taking out retirement at age 55 (if they live that long), and they had to play at least three seasons to be eligible (better be careful not to get a season-ending injury before then). Players who retired before 1993 are credited $255 a month for each season played, making a third of the amount that players who retired after 1993 get each month. Players who retired in 1993 (or earlier) don’t have access to things like annuities, 401ks, and improved insurance benefits (which is awful for retired players now, as it is).

Most of the funds paid each month go to healthcare – players’ bodies and minds are falling apart after playing football. The NFLPA recalls getting many calls in the early 1970s from panicked players who had been cut and were begging for loans to keep them afloat. Pauper funerals were common – many families had no extra money for funeral arrangements. This would have been legendary Hall of Famer Dick “Night Train” Lane’s fate if people hadn’t stepped in to help. The financial climate was challenging for a player at that time.

Isn’t it interesting that a constant through the five editions (articles one, two, three, and four here) is alleged stress around finances preceding each death(s)?Jovan Belcher was a Kansas City Chief too (curse???).

Personal hell

Jim was not doing well psychologically prior to the fateful night. Many different people noticed from all areas of his life. His children recalled that he had not been acting normally; they didn’t know what was happening and suspected he didn’t either. He had spent the last year of his career isolated – alone in Washington DC and playing through injury. Transitioning from athlete to retirement has always been identified as an emotionally challenging time for former players, and it was for Jim,

Unfortunately, pillar of strength Jim didn’t look like he was struggling at all until things got very bad. He didn’t have the vocabulary to explain his feelings. A friend said Tyrer was paralyzed in fear, unable to act or ask for help. He was quietly stewing six years later over being forced to go to a new team or retire by the Kansas City Chiefs – being replaced by younger players. This may be why he declined their scouting job offer post-retirement. Allegedly, the Chiefs were also withholding deferred money Tyrer was owed according to his contract – Kansas City denies this and says it wouldn’t help much with the debt, anyway.

Jim had many businesses at once – experiencing different levels of success for each one. A former teammate said that Tyrer stated he never gave a business enough of a chance, pulling out when he had just started making money and moving on to another one. He never had a reason why he didn’t stick with a successful business (we do, at the end of this article). Things only got worse after retirement – Jim was running a tire business from 1979 to 1980, but a mild winter that didn’t require snow tires for most left him in an even bigger financial hole.

The Tyrer’s did sell their house, and Jim was allegedly hawking Martha’s fur coats and selling Amway. It’s hard to sell items when he was dealing with noticeable “depression, irrationality, and erratic behavior.” At the very end, Martha was selling Amway too. A friend remembered that Martha insisted they meet each other, setting up a date to come over. Martha was also looking for regular work – an ironed dress was hanging in the room that night, waiting for a interview it would never attend.

Martha had never worked outside of the home before – now she was selling Amway, and looking for a full-time job. There’s no shame in that, obviously, but in an earlier time when gender roles were more defined and Jim was already in a bad place mentally, seeing his wife having to work because he couldn’t provide for his family likely only made his head space worse.

Friends noticed other usual behaviors in the months leading up to the tragedy. Tyrer had a strange preoccupation with the numbers on the scale – losing weight quickly and asking friends how he looked often. He would joke with friends that he could buy expensive things but then hint at being over $100,000 in debt, if not more. Other friends noticed paranoia – he was sure he had diabetes despite medical tests showing otherwise, and pain in one tooth meant he felt he was on the brink of losing them all.

Tyrer’s best friend recalls him being depressed five days prior to the end, attending job interviews, and feeling like he didn’t measure up to the young, recent college graduates he was competing with. On September 11th, his reverend and friend gave him the contact information for a therapist. Jim wouldn’t call… he was afraid he would get shock therapy. Brad remembers his dad giving him the talk the night before, alluding to him being the upcoming man of the house. Brad was just 17 and was literally measuring his bicep when his dad came in. He thought it was weird, but teens aren’t always particularly retrospective.

Jim took his son, Jason, to a Chiefs game on the afternoon of September 14th. Jason remembers two things – his dad hugged him, which was unusually affectionate, and his father was staring out at the field, oddly transfixed and preoccupied the entire game. Jason sensed something was off. He was right… Six to eight hours before his passing, Jim Tyrer had completed a psychological evaluation for a job that was later recovered. It was nearly impossible to decipher.

2nd historical moment (I see you excited over there, history buff!)

Our understanding of depression is constantly evolving, and we haven’t had a good grasp on it until the beginning of the 21st century. In the 1950s and 60s, depression was put into two camps – one was genetic, and the other was “neurotic” responses to environmental factors. A charming descriptor. Prior to the 70s, you were likely to receive a Freud-styled psychoanalysis.

The thought process in the 70s was that depression was almost exclusively physical and should be treated with medicine. Some of our favorite mother’s helpers (Prozac, Zoloft, and Paxil) weren’t around yet. Instead, newly developed drugs (TCAs) hit the market, and they were more effective than medicine before, but they made you gain weight and drool in your coffee.

It’s hard to imagine giant, emotionally closed-off football players being the trailblazers for breaking down the stigma surrounding therapy. Men and boys are still taught not to express their emotions as freely as women today, and we’re discussing a man who hugged his son for the first time at age 11 – Tyrer was an unlikely candidate.

Jim’s fear of electric shock therapy wasn’t unfounded, either – it was still commonly used in the 60s and 70s. Seeking mental help sounded terrifying at the time – new technologies were framed by the backdrop of exploratory treatments of the 40s and 50s, such as electric shock therapy, lobotomies, and hydrotherapy (AKA ice baths). Medicine was mostly heavy sedatives like barbiturates (all day sleepy time) in this era as well. Let’s just say there were many barriers to receiving mental health care for Jim that don’t exist today.

Martha Tyrer

Martha was born on August 18th, 1940, in Evansville, Indiana, to parents Truman and Lucille Cline. Little else is known about Martha’s childhood. Pat Livingston (QB Mike Livingston’s wife) was emphatic that Martha needed to be acknowledged for the incredible person that she was instead of being overshadowed by her husband. That sentiment is echoed here. We lost an incredible woman on September 15th, 1980, and she should be acknowledged as such. Pat and Martha’s children shared some things with us about her.

Martha, sometimes called Marty, was quiet, conservative, private and controlled. She was courteous, welcoming, and stable, always reaching out and embracing the wives of new football players. The women were close – they likely had similarly unique challenges being married to a Kansas City Chief. Despite being reserved, she couldn’t contain her excitement over a good game of Bridge, sweets, and a plate of Crab Rangoon.

The children remember Martha as a loving mother who went to all their games. Rumor has it that she was a lot of fun at McDonald’s, sneaking extra orders of fries to surprise her kids. Friends would say she was a wonderful mother. Jim would describe his wife as the positive in their marriage, and he was the negative. She was the glue that held Jim together, trying to keep him stable as he was unraveling. Martha didn’t understand his declining mental health state either. It’s unclear how much she knew about their financial situation (men in the 70s often handled family finances), but she knew she needed to help, so she did.

The morning of the 15th

The couple went to bed together like any other night. In the early morning of September 15th, 1980, Jim woke up and fumbled for the loaded gun the couple always had in the room for protection, shooting Martha and then himself. None of the children in the home were physically harmed.

The aftermath, the legacy

Martha’s parents moved into the house to take care of the children (seems like an ideal time to move…), providing love and security. Despite Jim murdering their daughter, Lucille and Truman didn’t seem to instill any negativity or resentment in the heart of the children. Tina also left college and moved back in with her family for additional support. The Kansas City Chiefs were a surrogate family, and the city also took seriously raising these children together. As of 2020, Jason Tyrer has been the best man in over 30 weddings from his Kansas City family.

Filmmaker Kevin Allen collaborated with Steven Hebert to create a documentary, “A Good Man – The Jim Tyrer Story” that was presented at a Kansas City venue in 2020. The story intertwines Jim’s origin story, the events leading up to the fateful night, and the Tyrer children’s life path since the tragedy. Allen met the Tyrer family in an unconventional way – Tina has been a successful hair stylist since the 1980s, owning her own shop and cutting the filmmaker’s wife’s hair for years. Allen was so impressed with the Tyrers’ he felt inspired to create the documentary.

There are many articles quoting the children, but they have communicated nothing but loving forgiveness for their father. The only negative emotion expressed was guilt over not noticing something was really wrong or not knowing more about neurological health at the time. It’s frankly almost baffling. They separated the murderer from their father, just seeing Jim as their dad. Stefanie used her loss to create perspective, acknowledging how many others experience more hardships. Brad had a spiritual moment at age 17 at his parent’s funeral, feeling grateful for having his parents for the years he did have, feeling a sense of peace, and replacing his sadness with gratitude.

Stefanie is a pediatric operating nurse. Brad got his dad’s aptitude for business – owning a successful flooring business in Louisville with his family of five. He was also an athlete like his dad, notably playing a few days after his parent’s death, making the winning kick, and leading his high school team to victory. Next, he played football at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln from 1983-1988. Jason continued to carry that torch, also playing in the Big Eight Conference for the University of Kansas as a defensive end from 1988-1992. Brad doesn’t believe that the four have lived remarkable lives, just the ones their parents raised them to live.

Ironically, in 1980, the NFL dropped it’s side of the funding for a two-day career counseling program for players because it was too expensive, leaving the NFLPA to pay it all or drop it entirely. The program ran for two years before the League dropped it. For former players, the conference felt like too little for a much greater need, and now it was gone. Did we expect any less, though?

Jim Tyrer was cremated, so the question many people are asking can’t be answered. Did the former player have CTE? Kevin Allen feels that Jim is patient zero for CTE (I disagree – people have likely been struggling with it since contact sports were a thing). Allen consulted with the Concussion Legacy Foundation, and they felt he demonstrated a text-book case of CTE. Jim’s children feel he had the condition, and some former teammates are confident that Jim had CTE too – he was the least likely person to do such a thing with his faculties intact. Tyrer’s brother-in-law isn’t so sure it was CTE, although he did know he was depressed – good thing no one cares, Al.

It isn’t hard to identify why so many feel he had CTE. The first stage of CTE is characterized by headaches, depression, and a lack of executive functioning (staying focused with distraction, making and meeting goals, and lack of self-control). Check. The second stage is associated with depression, executive dysfunction, mood swings, impulsivity, self-murder ideations, and language challenges. Also, check.

The symptoms identified in Jim’s life aren’t enough to prove that he had CTE, and even if he did, it doesn’t excuse his behavior. Although, it would be hard to see how a disease that impacts executive function, emotional regulation, impulsivity, aggression, and loss of self-control wouldn’t contribute to violent behavior. His brain resembled a slice of Swiss cheese if he had CTE – weird, inconsistent behavior feels like a given.

CTE wouldn’t even be identified for another 25 years and wouldn’t be understood for more. It’s truly saddening that men floundered in their own personal hell, not understanding why their mind was betraying them, subjecting their partners and children to that pain. I believe this is why the family, community, and football peers are not angry at Jim; there is a universal understanding that he was likely grappling with a disease that was more than he could handle, more than anyone can – at this point. CTE always wins (for now) – it’s fatal one way or another.