In honor of the last installment of Native American Heritage Month this year, Fritz Pollard who was the first to do it all will be highlighted.

Pollard is an incredible man of honor, that every person who professes to be a fan of football should know.

Fritz Pollard, born a legend from legends

John William Pollard and Catherine Amanda Hughes Pollard gave birth to Frederick “Fritz” Douglas Pollard in 1894 in Chicago. Fritz was the seventh of eight children, named after the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglas his parents had seen speak prior to his birth. Pollard’s parents had a strong commitment to civil rights, overcoming so many obstacles, and preparing their children to do so as well.

John Pollard was born to freed slaves in Virginia, and was sent to the Midwest with his sister at age eight due to his mother’s concern about people who were kidnapping and selling freed people of color into slavery. John was a professional wrestler before and during the Civil War. He was one of the first African Americans to join the Union Army in 1862 at just age 15. Post-service, John had plans to become a lawyer, but left Law School when he got very sick with smallpox. He decided to become a professional barber instead.

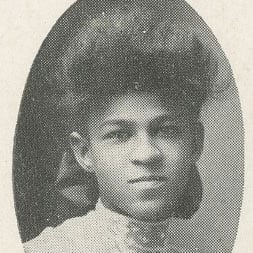

Catherine Amanda Hughes Pollard was a strong woman before her time. She was described as fully Native American in some sources, and described as African American, Sioux, and French in others. As a lady of the 1880’s, Ms. Amanda defied stereotypes for women, maintaining a fulfilling career as a seamstress for department stores. She also managed the family’s money, and her name was on tax forms and checks – a very rare occurrence for a woman in that time. Ms. Amanda did this all while being the glue that held her family together, birthing and raising eight children with her husband.

The power couple unilaterally decided to move to the Rogers Park neighborhood in Chicago, despite being the only “race group” in the area, according to reporters. They understood the importance of educational opportunity for their children and felt that the racism they experienced was tolerable with that goal in mind. Ms. Amanda would never answer the door without a gun in her apron, so that speaks to their experience, and makes her that much more incredible.

The children carried on their parent’s legacy of success. There is only information on seven of the eight children, one of whom dies young. Fritz’s eldest sister, Artissmisia, was the first black registered nurse in Illinois. His other older sister, Willie Naomi, was one of the first black women to graduate from Northwestern University. She later became a teacher, and then professor.

All the boys inherited their father’s athleticism. Fritz’s older brothers all helped teach him his football skills. His older brother Leslie vouched for him on the high school football squad despite his small size (5″7″). Older brother Hughes was a football genius as well but gave up the gridiron for music. He was a thriving touring musician in a jazz group throughout Europe, dying in WWI as a soldier.

Eldest brother, Luther Pollard was a multi-sport athlete star. He attempted to enter Major League baseball but was not allowed to due to being black and his inability to convince the scouts he was Native American which would have allowed him to play. He ended up being extremely successful – a multi-millionaire in today’s money due to his business – “Ebony Film Corporation” a moving picture production company.

Unfortunately, the Pollard’s accomplishments were rarely viewed in terms of their Native American heritage, so we can’t honor that part of their background with the same level of completeness. It was to the point of people outright denying that part of them, such as in the case of Luther Pollard and his baseball career. The children were able to avoid boarding schools that were popular in their time, but it also barred them from certain career opportunities.

Why Fritz Pollard’s football career was defined by his African American heritage, but other Native Americans in the league at the time such as Jim Thorpe or Joe Guyon were defined by their Native American Heritage and not other parts of their ethnic background, is unclear. These arbitrary rules surrounding 1920’s racism will not be present in this article, Fritz attributed his success to his ancestors, and we will be honoring them all.

Fritz Pollard – The Athlete

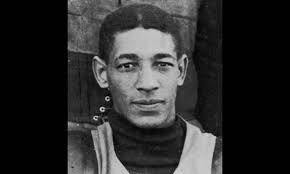

Despite the family being such an athletic bunch, the Pollard men were small and slight in stature. Fritz was 5″7″ and 166 pounds, and the football coach at Lane Technical High School thought he was too small to play on the team. Luther Pollard had to vouch for Fritz’s skills and said he wouldn’t play if his little brother couldn’t. With a little bit of brotherly love, Fritz graduated from high school at 18, a multi-sport athlete. In addition to being a running back, he was a baseball player, and a three-time country track champion.

In a feat that is no longer possible with current collegiate rules, Pollard played for Harvard, Dartmouth, and Northwestern for a short period of time. He then attended Brown University after he got a full ride from the Rockefeller family in exchange for playing football and participating on the track team. He would play until 1918 when he dropped out due to being disqualified from play due to academic probation

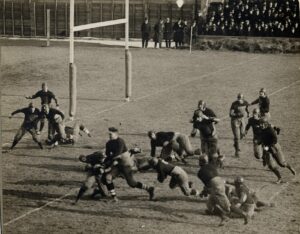

Fritz was the first African American and Native American to play in the Rose Bowl in 1915. He had 12 touchdowns and was selected by Walter Camp to participate in the All-American team in 1916. He was the second ever African American to be selected for this team, and the second Native American player to be. He was between Jim Thorpe and Joe Guyon for this accomplishment – impressive for all three. Also in 1916, Pollard set a record for low hurdles at Brown, and qualified for the Olympics. He didn’t compete due to the games being cancelled because of World War I.

The facts and stats don’t speak to the incredible turbulence that swirled around Pollard in collegiate sports. He had to face unspeakable racism. His teammates at Brown didn’t want him there – they wouldn’t even speak to him. Somehow, his personality and skill won them over according to his grandson. He would have 60-80 rushing yards regularly when he was in possession of the ball with baggy pants flapping endearingly as he ran due to his small size.

The game of football was a violent sport in 1915 – punching, kicking, and eye gouging were all common on the gridiron. Fritz got more of his fair share of all of those things in addition to verbal abuse due to his race. His grandson said he learned how to prevent people stepping on him and attempting to cut him with their feet by rolling on his back and kicking his feet out like a cat.

Fritz’s teammates had his back at every turn, as they obviously should have. It’s not ideal to give players a hero complex for maintaining basic human decency, but in the 1910’s racial climate it was significant. Pollard’s grandson says that men would dress up in baggy uniforms so everyone’s uniform looked as big as Fritz’s.

In the strangest case of black face in the history of America, Fritz’s teammates would put shoe polish on their faces as another attempt to confuse opposing players on which player was Pollard. For a multitude of reasons, neither idea seems particularly helpful. But this was also football in the years when the forward pass hadn’t been made legal for 10 years yet, and players died on the field, so maybe it did provide some physical protection for Pollard.

Fans proved to be a bigger problem. The team faced death threats at different schools, including Ivy League schools, across the country. Dr. Steven Towns, another grandson of Pollard, remembers that Fritz would have to be escorted onto the field by policemen. Yale fans would sing “Bye Bye Blackbird” when he would enter the field.

The Rose Bowl was eventful as well – the hotel would not allow Pollard to stay at their facility. If Fritz was not allowed to stay at the same hotel, Brown University decided the entire team would up and leave Pasadena, California and go back home. None of his other teammates would agree to stay in the hotel either. The hotel finally yielded, and everyone stayed in the hotel. See how easy that could have been, Pasadena?

Fritz Pollard has a life transition

Between 1916 and 1920, Fritz was doing it all.

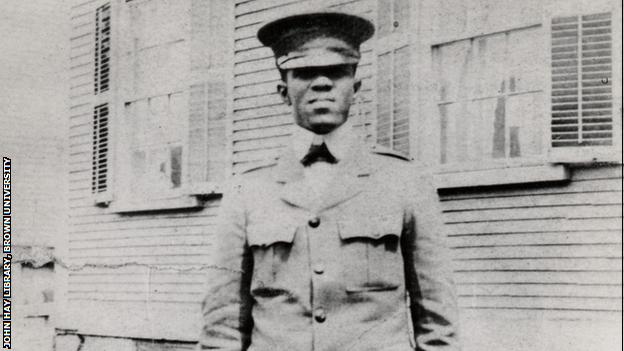

He was in the army for a short time, and was the director of an army YMCA. He also tried and decided against going to dental school.

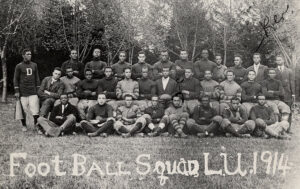

Pollard then became the head coach for the Lincoln University football team from 1918 to 1920. He lead the team to many victories, but he got blowback for missing a few key games that resulted in shut out losses. Fritz had missed these games in result of playing in the NFL for the Akron Pros.

Pollard didn’t appreciate the criticisms though – he pointed out that he had to have a second job because his coaching salary was so low, he had to spend his own money to buy the team supplies and had to boat with his team to an away-game, sleeping on decks and under portholes. No cabins were supplied. The coach and university parted ways at this point.

Fritz Pollard goes pro

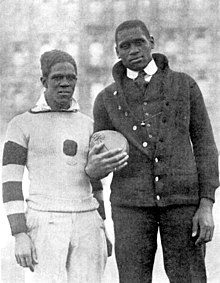

Fritz was one of the two black players in the NFL. He was one of three Native Americans in the League.

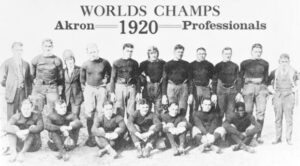

Pollard has all the firsts in the NFL:

- First black quarterback in the NFL – the only qb until George Taliaferro in 1950.

- First Native American quarterback in the NFL until Jim Plunkett in 1971

- Tied with Jim Thorpe as the first Native American head coach in the NFL – both began their position in 1921. They are debatably the only Native American head coaches ever. William Henry Dietz may have been another Native American coach in the league (there is controversy) who was a head coach in 1933-1934.

- The first black head coach of an NFL team and the only coach until Art Shell in 1989.

Fritz would bounce around playing on different teams. He was an Akron Pro from 1920-1921, a Milwaukee Badger in 1923, a Hammond Pro in 1923 and 1925, and then rejoined Akron from 1925 to 1926. He also played on other professional teams outside of the NFL throughout that period of time. He coached two teams in the NFL – the Akron Pros in 1921 and the Hammond Pros in 1925 – both while playing. Pollard would coach as many as four teams in one year. The salaries were low, but not quite that low, Fritz was just a powerhouse. He actually was one of the highest paid players and coaches in the league.

It’s a bit difficult to compare Pollard’s stats with the modern-day stats – the game was very different. But what we do know is that Pollard deserves all the accolades and then some. He was an elite player in the league at his time and was an elite human off the field as well.

More racism for Fritz Pollard

Fritz’s NFL career ended suddenly in 1926. This wasn’t because Pollard was ready to tip his hat and say goodbye to the league. No, it was because all African American players were banned from the league in 1926 by most of the 1963 NFL Hall of Fame enshrined players. Fritz mentioned he felt George Halas was one of the greatest foes of black football players and was the force behind the ban.

All Native American and African American players were cleared out of the league before the Great Depression – this is due to the fact that White Americans didn’t appreciate seeing men of color having jobs playing football, when they didn’t have work. Say you’re a pathetic excuse for a human without actually saying you’re a pathetic excuse for a human.

Pollard coped with racism by looking at the haters and grinning, kicking their can in the next play. Jim Thorpe didn’t appreciate this method – he asked Fritz if he knew who he was, and obviously Pollard did. Thorpe said he knew who Fritz was too and called him the N word. Pollard called him the N word back. The ultimate power play.

Jim really had a hair in his butt this day because he then threatened to kill Fritz. Pollard responded by saying he could come find him in Thorpe’s end zone when he was ready to do it. Fritz shut that whole interaction down when he got a touchdown with the first kick off and waved to Thorpe from Jim’s end zone to come on over.

Jim said Fritz was one of the best backs he’s ever seen. It’s a really good thing Pollard was such a good player because he had to earn the respect from his peers with good play every other second. Fritz would actually have to change into his uniform in his vehicle, because he wasn’t always allowed in the locker rooms.

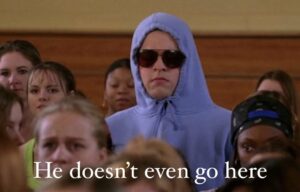

George Halas said he would never play against a team with a N-word on it ever again. Oddly, Halas’s hatred seemed to make Fritz more popular with the fans, although not necessarily admired. Halas is like that one drunk great uncle in the holidays that everyone wants to throw out with the turkey bones. He had the nerve to say that African Americans hadn’t played in the league for over 20 years because the game wasn’t appealing to them. Do you even go here, George?

Fritz Pollard finishes football

After being booted from the NFL, Pollard created two all-black barnstorming teams. The Chicago Black Hawks was started in 1928 that succumbed to the Great Depression, and the Harlem Brown Bombers that was started in the 1930’s.

These teams played against other pro teams, outside of the NFL. The Harlem Brown Bombers did so well they actually had to underperform to avoid beating white teams to badly. The Bombers were afraid that people wouldn’t play them if they played to their full capabilities. The team had a record of 29-0 according to his grandson, Dr. Towns.

Fritz Pollard sweeps the business world

Pollard dominated the business world as much as he did football. He somehow had the time to create the first black-owned investment firm that served the African-American community from 1922 to 1931. He also had a coal business. In 1935, Fritz created the first black tabloid that ran from 1935 to 1942.

Fritz may have taken music and film inspiration from his brothers Luther and Hughes. Pollard was a casting agent, and also produced “soundies,” which were short music videos of black entertainers.

Fritz did dapple with politics a little bit – he was an awkward intercessor between friends in the Republican party like Rockefeller and others like Nixon and the African American community…

It’s difficult to know if he was one of the first to do these things in the Native American community, but he was a trailblazer for that community as well, even if it goes mostly ignored in these “firsts.”

Fritz Pollard’s personal adult life

Pollard married his first wife Ada Laing in 1914, whom he had three daughters and his son Frederick Douglas Pollard Jr. with. His daughters apparently have no names as they aren’t available anywhere. He remarried in 1947 to Ms. Mary Ella Austin. He had energy for all life had to offer.

The legacy Fritz Pollard left behind

Fritz Pollard left behind a incredible football legacy that has often been overlooked and understated. He was enshrined into the Hall of Fame – but not until 2005. He also made an footprint in the business world too.

Pollard was an active father and grandfather and remains a prominent memory in his grandchildren’s lives. His son Fritz Pollard, Jr., was also an incredible athlete amongst other things.

The neighborhood Fritz grew up in is attempting to honor the family with a park near Pollard’s childhood home.

Pollard also lives on today in the NFL through the Fritz Pollard Alliance that exists today. This foundation works on promoting equal opportunities for minorities in coaching and front office positions.

Fritz Pollard was quoted as saying that football is not a game, it’s a religion. Pollard can be our spiritual leader to the gridiron in the sky any day. We lost the man that the world did not deserve in 1986, at age 92.

For other Native American Heritage Month content look here, here, and here.